What does the Money Market looks like?

In macroeconomy, the link between money supply and inflation was established. Why do we need inflation? Wouldn’t gold standard do? Apparently, if the mandate of the federal reserve is to defend a gold peg, they can do it by letting the employment and inflation fluctuate. In the 20th century, what they discovered is that this constraints would break during crisis time such as the 1930s and the 1971 (the Nixon Shock). Someone wrote a paper looking at he 20th century history through the lens of finance, and proposed the idea that should they moved away from the gold standard at appropriate time and allowed the economy breathing room, those world wars could have been avoided.

On the one hand, a gold standard based monetary policy would exert depressionary pressure on the economy. On the other hand, too much money printing would result in hyper inflation. So the mandate of federal reserve is to target a moderate inflation rate (the newest target is aggregated 2% inflation annually) while maintain a high employment rate.

There are three tiers of monetary policy. Lowering interest rate, such that all the assets with future cashflow would have be evaluated at a higher current price, which would lend itself to higher borrowing power. All the debt can also be refinanced at a lower rate, which makes it easier to service. The second tier of monetary policy is put things onto federal reserve’s balance sheet. This is a relative new style of monetary policy started since the 2008 financial crisis. Now the COVID stuff brought about the third tier monetary policy: minting new money.

In the most traditional view of financial system, banks are the only intermediary between the money printer and those who need it. However those days has long gone. Interest Rate Swaps, Credit Default Swaps and a slue of other instruments plays the role of striping away risk from a set of cash flow. Theoretically, bank is the only institutions capable of issuing credit, but that is clearly no longer the case with all sorts of shadow banking.

On a side not, why during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 covid crisis, there is no inflation risk even with all the QE and money printing? because the money printing barely made up for the decreasing in credit market.

The game of monetary policy is to maintain a balance between debt accumulation and earnings stream. The most idea situation would be the newly minted money or credit goes to activities which create a new set of cash flow, i.e. expanded the economy. However, most of the time people use the money for financial instrument purchase such as housing. The worst case scenario would be all the newly created money/credit goes into financial instrument without expanding the economy at all. That way, the price of financial assets goes up but would also set the stage for a eventual crash.

When it comes to bubble, it is actually no one’s fault. When the music playing, you have no choice but to dance. That is the only rational choice. Check out this Mervyn King interview. In the beginning part of the interview, he reflected how even though all those people at the Bank of England can see trouble brewing in the background, they can’t really do anything about it because if they raised the interest rate, and no one else does. Then given the FX mechanism for importing inflation, then that would be a losing bet. The problem with a system like this is that even though you can see the tsunami coming your way, you can’t really do anything about it because the only rational choice is to keep doing that would inflame the situation. Also Perry G Mehrling’s Money View is quite informative when it comes to understand crisis.It look at the system from a market maker’s perspective.

When it comes to investment, the Ray Dalio’s all weather fund has a interesting thinking framework behind it. In his mind there are two drivers for asset valuation increase. One is inflation, another is growth. The price is set by the expected growth and a sudden price change would result from changes in expectation. When the growth rate is greater than expected, then equity does better. When the growth rate is lesser than expected, then bond does better. A contigency table approach is used to be future proof. Sort of like there are known forces to drive the price up, structure the portforlio such that no matter which force takes the upper hand, over all, the return from this entire portfolio is the same regardless of the circumstances.

My intuition is that the entire setup is way too self-perpetuating. During the upward phase of the cycle, the most minis-cure source of income can be multiplied manifolds but the only real place to place that debt is non-productivity increasing element of the economy such as the real-estate. As a player in that system, that choice isn’t really yours to make because that is actually the only rational choice at that point. The real productivity increasing activity has near zero yield. One of the common complaint during the downside of the cycle is that the line of liquidity vanished overnight. Of course they would vanish overnight, they should not have been there in the first place.WHO THE FUCK DESIGNED THIS SYSTEM TO BEGIN WITH?

Why when anything is formalized as a system, there is always an impulse to overdone it? What can be said in 10 pages just have to be said in a 1000 page book. What could have been a reasonable credit system would be magnified to the extend it is.

Here is where I come down at the economic life: there is going to be a group of people who shape the economic system into a modern one. They can win big or loose big. I am going to stay out of it.

One thing really stunt me is that everything in financial system feeds on each other, no wonder it go through violent cycles. For instance, when the Fed cut the interest rate, banks generate more creditwhich eventually made its way into asset market, rasing the prices for financial assets. Not only that, the asset pricing scheme, which is based upon the discounted cashflow model, would raise all asset prices cross the board since the time value of money, ie. interest rate is lowered. the action of lowering interest rate manifest itself multiple times through out the system, and every component feed on one another in a possitive feedback. Who freaking comes up with this system?

Coronavirus crisis lays bare the risks of financial leverage, again

Crises reveal fragility. This one is no exception. Among other things, coronavirus has revealed fragilities in the financial system. This is unsurprising. As before, reliance on high leverage as a magical route to elevated profits has led to private profits and public bailouts. The state, in the form of central banks and governments, has come to the rescue of finance on a gigantic scale. It had to do so. But we must learn from this event. Last time, it was the banks. This time we must look at capital markets, too.

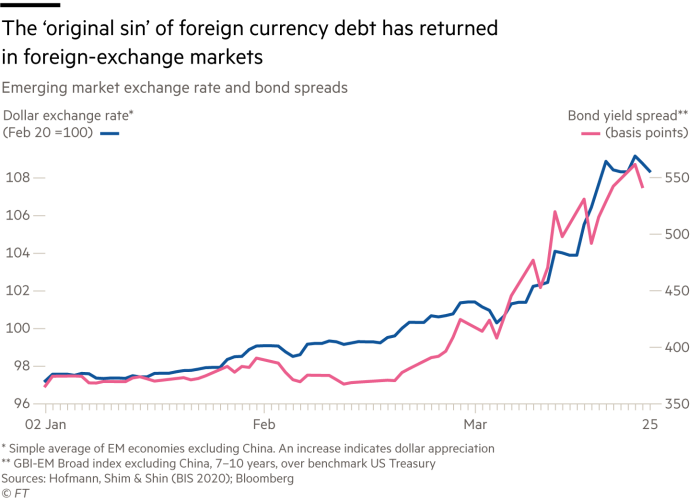

The IMF’s latest Global Financial Stability Report details the shocks: falling equity prices, soaring risk spreads on loans and plummeting oil prices. As usual, there was a flight to quality. But liquidity dried up even in traditionally deep markets. Highly-leveraged investors came under severe stress. The pressures on the financing of emerging economies have been particularly fierce.

The scale of the financial disarray reflects in part the size of the economic shock. It is also a reminder of what the late Hyman Minsky taught us: debt causes fragility. Since the global financial crisis, indebtedness has continued to rise. In particular, the indebtedness of non-financial companies rose by 13 percentage points between September 2008 and December 2019, relative to global output. The indebtedness of governments, which assumed much of the post-financial crisis burden, rose by 30 percentage points. This shift on to the shoulders of governments will now happen again, on a huge scale.

The IMF report gives a clear overview of the fragilities. Significant risks arise from asset managers as forced sellers of assets, leveraged parts of the non-financial corporate sector, some emerging countries, and even some banks. While the latter are not the centre of this story, reasons for concern remain, despite past strengthening. This shock, the report states, is likely to be even more severe than envisaged in the IMF’s stress tests. Banks remain highly-leveraged institutions, especially if we use market valuations of assets. As the report notes: “Median market-adjusted capitalisation is now higher than in 2008 only in the US.” The chances that banks will need more capital is not small.

Yet it is capital markets that lie at the heart of this saga. Specific stories are revealing. The Bank for International Settlements has studied one weird episode in mid-March when markets for benchmark government bonds experienced extraordinary turbulence. This happened because of the forced selling of Treasury securities by investors seeking “to exploit small yield differences through the use of leverage”. This is the type of “long-short strategy” made infamous by the failure of Long Term Capital Management in 1998. It is also a strategy vulnerable to rising volatility and declining market liquidity. These cause mark-to-market losses. Then, as margin is called in, investors are forced to sell assets to redeem loans.

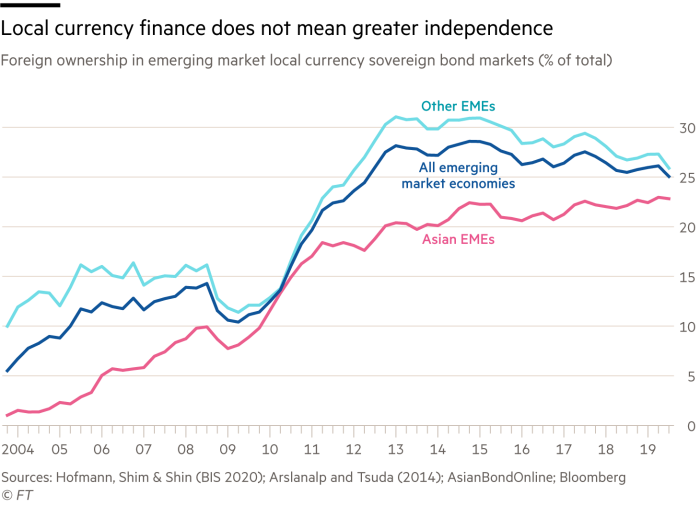

Another story elucidated by the BIS tells of emerging economies. An important recent development has been the rising use of local currency bonds to finance government spending. But when the prices of these bonds fell in the crisis, so did exchange rates, increasing the losses borne by foreign investors. These exchange-rate collapses worsen the solvency of domestic borrowers (notably businesses) with debts denominated in foreign currency. The inability to borrow in domestic currency used to be called “original sin”. This has not gone, argue the BIS’s Augustin Carstens and Hyun Song Shin. It has just “shifted from borrowers to lenders”.

Yet another significant capital-market issue is the role of private equity and other high-leverage strategies in increasing expected returns, but also the risks, in corporate finance. Such approaches are almost perfectly designed to reduce resilience in periods of economic and financial stress. Governments and central banks have now been forced to bail them out, just as they were forced to bail out banks in the financial crisis. This will reinforce “heads, I win; tails, you lose” strategies. So vast is the size of central bank and government rescues that moral hazard must be pervasive.

The crisis has revealed much fragility. It has also demonstrated yet again the uncomfortably symbiotic relationship between the financial sector and the state. In the short run, we must try to get through this crisis with as little damage as possible. But we must also learn from it for the future.

A systematic evaluation of the frailties of capital markets, comparable to what was done with banks after the financial crisis, is now essential. One issue is how emerging economies reduce the impact of the new version of “original sin”. Another is what to do about private sector leverage and the way in which risk ends up on governments’ balance sheets. I think of this as trying to run capitalism with the least possible risk-bearing capital. It makes little sense. This creates a microeconomic task — eliminating incentives for the private sector to fund itself so heavily via debt; and a macroeconomic one — reducing reliance on debt to generate aggregate demand.

The big question now is whether the essential systems that keep our societies running are adequately resilient. The answer is no. This is the sort of question the OECD’s New Approaches to Economic Challenges Unit has dared to address. Inevitably, it has created much controversy. Yet it is admirable that an international organisation is daring to do so at all. The crisis has shown us why.

We cannot afford complacency. We need to reassess the resilience of our economic, social and health arrangements. A focus on finance must be an important part of this effort.

China’s economy can only grow with more state control not less

China’s People’s Daily recently announced major new guidelines to improve the economy’s market-based allocation mechanisms. These measures signalled Beijing’s determination to liberalise the economy and implement supply-side reforms that will strengthen the private sector. They follow several years of slowing growth and surging debt, both likely to be made worse by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Mainstream economists have long called for Beijing to improve China’s market mechanisms, and they have deplored the rolling back of the private sector over the past decade. But despite years of supply-side proposals and repeated reform pledges, there has been little evidence of a substantial reversal in the trend towards greater government control of the economy.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone. Over the long term, Chinese growth might indeed benefit from a stronger private sector and a more market-oriented economy. Yet in the near and medium term, this approach will do almost nothing to address either the real causes of China’s slowdown or its growing reliance on debt. Nor would it diminish Covid-19’s economic effects.

This is because China doesn’t have a supply-side problem. It has a demand-side problem, which the coronavirus pandemic has only made worse. What is more, the rolling back of the private sector in recent years is a consequence, not a cause, of China’s underlying demand-side problem.

Until this problem is resolved, it will be almost impossible for Beijing to reverse course and overturn the trend towards greater government involvement in the economy.

Economists have known since at least 2007, although perhaps they have forgotten in recent years, that China has an extremely unbalanced economy. At the heart of this imbalance lies the very low share of income that ordinary households retain of China’s gross domestic product, compared with that of local governments, businesses and the very wealthy.

At roughly half of GDP, it is among the lowest of any country in history. As a result, sustainable household consumption, typically the largest component of overall demand in a large economy, also drives a very low share of total Chinese demand.

This low consumption has knock-on effects on private-sector investment. Most private investment goes either to increase export capacity or to serve consumption. Yet exports were never going to persist as a major source of growth in a large economy such as China’s, and today its prospects are dimmer than ever. At the same time, the relatively low share of household consumption constrains private investment too.

In other words, the healthiest sources of demand — consumption, exports and private-sector investment — are together unable to generate the level of growth that Beijing considers to be politically necessary, which until recently was deemed to be 5 to 6 per cent.

So what are the other sources of growth? In China’s case only two: infrastructure investment and real estate development.

With China already massively overinvested in infrastructure, only the government will directly or indirectly promote more. Meanwhile the real estate sector, with nearly one-quarter of all urban apartments already empty, is also crucially dependent on state support. Because an economy in which resources are allocated by market forces is unlikely to devote much effort to either sector, the only way to keep growth high is via more state support.

This is why the state has played and will continue to play an expanding role in China’s economy. As long as Beijing requires growth that is substantially higher than the economy’s real, underlying growth rate (probably around half reported growth rates) China has no choice but to expand the government’s presence. This will also reduce the market’s role in allocating resources.

Market-based reforms, no matter how aggressively implemented, will not drive sustainable growth in China. An economy in which the market allocates resources and capital can generate high growth rates. But only after Beijing completes a politically difficult but necessary redistribution of wealth — and with it power — from local governments and elites to ordinary households.

Local elites have long resisted this. But without it, promises to reduce government control in China’s economy and to increase the role of the markets will remain empty. Until demand is rebalanced, only expanding the government sector and increased debt can guarantee high levels of growth.

The writer is a finance professor at Peking University and a senior fellow at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center

- the methods economists utilize to analyze a problem is worthy of attention. First, they have an observation. For instance, why money seems to go from developing economy to developed economy? Then, device a dynamical system that is as simple as it can be to explain the observed pheromone. There are all kinds of interesting toy models, island economy with only 2 agents etc.

- Futures market as a price discovery mechanism. The method they used to mitigate risk is thoughtful. You have to put up collaterals if you want to trade in the future’s market. Therefore, if your circumstances don’t allow you to carry out the transaction in the future, then you would be kicked out of the market before that risk is realized. This market solution to mitigate risk is something could be applied to other problems.

- Derivatives are insurance with specific trading constraints. The idea of a housing price put is quite practical. I wish we can have similar products here.

- Dynamic heading is a reasonable concept. Every time interval, your hedging strategy can be adjusted, and cash-flow reconstructed.

- Looking at the demographical trend, I have one question. There is not gonna be enough workforce to keep the system going. They probably need to adapt some sort of immigration scheme to get workers from Africa, and the Muslim population.

- I agree Michael Pettis’ definition of rich country and poor country. The former have infrastructure, institutional or hardware that allow people to create more value. Chinese government can pretty much set the GDP number to whatever they deemed reasonable, coz the way they compute that number is how much money they invested in. That is a horrible way of computing output. For instance, a bridge to nowhere would not cultivate more productive output, but it is computed as part of GDP. He thinks that the optimal amount of hardware investment is where the population can generate commensurate amount of productive output. China has long passed that point. There might not be enough cash-flow to service the accrued debt.

- Financial Suppression. A term coined by Michael Pettis and I can feel it. The inflation just went out of control, money today is by no means money few years ago. There are no investment instruments other than housing. Investment overseas is banned since 2016.

摘 要: 在新冠肺炎疫情背景下,特别是近几年主要发达经济体的经历与实践显示,低通胀对于央行货币政策操作和理论框架提出了挑战,也动摇了通胀目标制的理论基础。通胀既是央行观察经济金融状况的终极变量,也常是一个中间变量。传统的通胀度量会面临几个方面的不足和挑战:较少包含资产价格会带来失真,特别是长周期比较的失真;以什么收入作为计算通胀的支出篮子;劳动付出的度量如何影响通胀的感知;基准、可比性(comparability)和参照系。当前不少国家的货币政策面临着不能有效达到通胀目标的问题。需要明确要达到的目标,以及如何对目标进行测度。测度对于经济社会而言是相当复杂的,可能需要更广义的通胀概念;如何对通胀进行测度,值得进一步深入的研究。

关键词: 通胀率 货币政策 可支配收入 物价指数 资产价格

在新冠肺炎疫情背景下,特别是近几年主要发达经济体的经历与实践显示,低通胀对于央行货币政策操作和理论框架提出了挑战,也动摇了通胀目标制的理论基础。这涉及到多方面的问题,其中重要的关注是,主要发达经济体货币政策框架是否能够适应当前经济金融形势的需要,涉及货币政策的理论和实证依据问题,比如经验的菲利普斯曲线是否已经彻底失效等。近日Dr.RichardC.Koo(辜朝明)在一次访谈中说到,通胀目标制现在基本上没有用了,甚至可能带来资产泡沫。这些问题都引起热烈的讨论,特别是央行货币政策应该如何应对疫情下的经济金融形势和当前低通胀率。

货币银行学教科书教给大家的一个基本经济规律是,过量(超过GDP增速)的货币扩张会带来通货膨胀。但近来这个规律似乎正在失效,形成对基本知识的重大挑战。从逻辑上来说,有三处可能出现差错:一是货币概念和范畴可能变了;二是从货币到通胀的映射关系出问题了;三是通胀的概念、范畴和度量出了问题。前两种问题已有一些学术讨论,在此讨论一下第三种问题。这是一个较少受到关注的议题:当前低通胀率本身是否存在概念上和度量上的疑问?是否如多数人估测的通胀未来将会长时间维持低位,它涉及到我们应对低通胀的对策有没有问题。多年来,通胀率的度量在传统轨道上不断改进,对物价指数涵盖的篮子进行动态调整,技术上应该说是科学的,很难有可挑剔之处,但以它来评价货币政策的有效性还有进一步讨论的余地。

我首先想问的是,现行概念和度量上的通胀率是否是最终要观测的目标变量?当前通胀率的指标究竟是我们想要最终观察的经济指标?还是一种中间变量测度?对货币政策而言,它究竟是一种充分综合的经济变量,还是只是多个经济度量指标之一?在观察社会经济动态变化过程中,我们经常采用对中间变量进行测度,但中间变量并不是最终所关心的内容和度量目标。不过,时间长了,人们会习惯性地认为中间变量就是最终观测目标。比如说,过去许多央行用测量M2去度量货币扩张的程度,后来发现这一对应关系不那么稳定,导致要修改M2度量的定义和内容,或另寻出路。就通胀而言,也有几种指标(物价指数有消费者物价指数(CPI)、投资品物价指数和GDP平减指数,均指向最终产品与服务。生产者价格指数(PPI)则包含中间投入品),用于不同的分析场合。

举个工程上的例子,在测量温度时,一个传统的测量方法是用水银温度计,水银体积随着温度高低变化而出现膨胀或收缩。另外一种测试方法是利用双金属片温度计,两类金属在温度变化时的膨胀系数不一样,这个差异产生的形变使得温度计指针能够标出所测的温度。不过,在一些场合,比如金属冶炼中,需要测很高的温度,上述两种测量就不管用了,温度过高后水银会蒸发,双金属片会变软。实际上,我们需要找到另一个中间变量,比如某一观察对象的颜色,它和欲测量的高温之间有一定的数学关系,或者说是一种映射关系。这种映射关系如果是一一对应且稳定的,测试中间变量就能得出对高温的度量。但这种一一映射关系是否稳定,是否在某些条件下会发生变化,值得关注。因为如果因条件变化使映射关系不稳定,这个对高温的测试就不准了。

总体而言,通胀既是央行观察经济金融状况的终极变量,也常是一个中间变量。央行关注通胀的目的,可能是关心提高居民福祉的程度,促进经济体系稳定运行的程度,改善公众对经济系统未来稳定预期的程度。在美国竞选辩论中,拜登批评特朗普时用了一个词,costofliving(生活成本)。这和想象中的广义通胀有些相近,这是个较模糊的概念,但也许正是人们最终关心的。个人认为它包含两方面的内容:一是特定的收入能购买到什么样的生活水准,这既包括特定篮子的物价指数,也包括篮子有什么重大变化;二是通过工作赚取特定收入的代价,是十分艰辛、疲惫呢?还是较为从容、轻松甚至愉快?这种综合又有模糊性的概念在影响着人们对未来的预期,对未来是乐观还是悲观。通胀是要度量的变量之一,不一定是评价居民福利、经济运行的全部,而货币政策肯定应考虑通胀指标背后的体验。

从测度的角度来看,我们平常利用通胀率这个指标究竟想知道什么?按“生活成本”的上述理解,可能主要有这么几项:第一,经物价校正后的真实收入究竟怎么样?究竟增加了多少?真实收入跟名义收入有所不同,名义收入要扣减通胀才能得出实际收入。第二,用可比的同等收入能购买到什么样的生活水平?我们是否日子过得比以前更好?一种是跟上一年纵比,一般来说一年期间的支出结构变化比较小,较容易扣减通胀。另一种是跟更久一点的过去相比,比如,我们是否比上一代人活的更好。比较的跨期越长,难度也更大一些,因为支出结构发生了巨大的变化,不仅涉及货物与服务,可能还涉及更多内容。第三,换取同等实际收入的劳动付出的强度,是更辛劳、疲惫?还是更为从容、轻松?这可以表达为劳动付出与效用的关系。这里说的付出,指的是劳动者在一定的生产力条件、效率条件下,付出多大努力获得特定量的收入,简化来讲也可以用劳动时间来衡量。同时它给劳动者/家庭带来的效用究竟如何?人们现在的支出能力确实比以前强了,但如果天天加班加点,上下班交通很艰难、耗时,周末也较少休息,这样的话付出会较大。因此,付出与效用之比也是关心的内容,也需要借助通胀来进行观察,但显然不限于通胀这一项。

总之,一般来说,通胀在概念上是一种最终变量,但有时其度量的是一种中间变量,和我们的最终关切不完全吻合;同时,通胀只是要密切观察的变量之一,还有其它需要观察的变量。

表面上看,跨年度的通胀度量是可信的,没什么技术上的问题,但细想一下,也存在某些挑战。多年度或跨代的生活成本比较,篮子结构已有重大变化,度量的可比性会面临挑战,特别是对那些从无到有或者从有到无的科目,其基准已发生重大变化,如寿命(涉及养老、医疗等)、就业技能、计算机与网络、旅游娱乐等等。用年度复利的通胀也难以有效比较。此外,面对世界人口激增、城镇化激增,导致城市用地紧缺、价格大幅上涨,传统的居住价格能否有效反映居住成本,也是人们反复质疑的。传统的通胀度量会面临几个方面的不足和挑战:

一、较少包含资产价格会带来失真,特别是长周期比较的失真

通胀在针对短期经济现象方面,月环比、年度同比等指标还是很不错的。不过,在实践中也遇到很多的疑问和挑战。从长期看,当前通胀度量问题中一个突出的瑕疵是,对投资、资产的价格度量覆盖比较少,权重比较低。按照过去的概念体系,与消费者有关系的主要是消费者价格指数(CPI),消费者似乎不太关心投资,投资主要与企业和企业家有关系,资产贵了,与CPI的关系不密切,但实际上资产贵了一定会影响今后生活。如果资产贵了,养老投资的回报就会降低。纽联储上一任主席WilliamDudley(他也是G30成员,2009年继TimGeithner接任纽联储主席,上一轮危机处理基本上都有他参与)近期就新冠疫情讲到,“当利率长期维持低水平时,该(宽松)政策会适得其反。在美国,货币刺激已经将债券和股票价格推至如此高的水平,以至于未来的回报率必然会更低。假设估值稳定,未来十年的预期股票收益率可能不超过5或6。10年期美国国债0.7的收益率甚至无法补偿预期通货膨胀率。结果就是,人们必须增加储蓄才能实现自己的目标,无论是安全退休还是供孩子读大学。消费支出会变得更少。即使人们现在不存钱,低回报率也最终会造成损失。例如,州和地方养老基金的钱将不足以履行养老金支付义务。为了弥补差额,官员们将不得不提高税收或削减养老金领取者的福利。任何一种行动都会使人们变得更穷,从而压低消费者支出和经济增长”。

对于住房,过去的概念是购房算作投资,价格变化不计入CPI;后来则租房可计入,但在篮子中的权重偏小;再后来,人们主张把自住房用类比租金来计量,但是住房权重仍相对比较小。当全球人口上升到70亿,城镇化成为相当多数人生活、工作的必然选择,城市可用地变得很稀缺且价格高昂,使得通胀度量再也不能无视或者低估住房的因素。总之,通胀在长期度量上存在问题,特别是资产价格如何反应到生活质量、支出结构上。此外还有长期投资回报应折现入当期通胀的问题。

在美国,目前有不少中部地区的白人对生活很不满意,他们谋求变革,造成美国政治和选举方面有很多的变化。一个因素就是中部的美国白人不觉得比上一代人过的更好,这需要用房子、车、教育、医疗、养老等长期支出来进行综合衡量,这种比较是长期性的。前面WilliamDudley的话中就提到了供孩子读大学的问题。上一代美国人多供几个孩子上大学没太大困难,现在有不少人说有很多困难,一是标准提高了,另外确实有些涉及教育的价格是很贵的,特别是私立学校,还要争取名校,还需要有很多课外补习班。从这个角度来讲,人们在这方面不见得比过去活得更好。显然,现行通胀的度量没有很好的解决这些问题。

二、以什么收入作为计算通胀的支出篮子

目前,CPI的支出篮子是家庭可支配收入。首先粗略定义一下收入:厂商和个体经营者的毛收入指销售收入;扣除投入品成本后为税费前净收入,简称净收入,它与GDP中的附加价值相对应;受雇劳动者的劳动应得再交所得税、社保费、医疗保险等(不论是预扣、企业代缴还是个人/家庭缴纳)后,形成个人/家庭可支配收入。其实,家庭/个人生活水平及质量有相当一部分来自于不可自行支配的收入,包括通过交税而享用的公共服务、预筹积累的养老金、强制性保费等。我们有没有想过,如果这些不可支配收入所对应的项目变得价格更昂贵了,是否也应纳入通胀呢?这部分开支在毛收入中的比重已不可忽视。例如纳入公共统筹的预筹养老金很可能通过不同渠道从劳动者所得中上交了,一部分是雇主代交的,一部分是雇员交的,往往都在家庭可支配收入之前,但又成为消费和生活质量的重要组成部分。在美国,医疗健保总支出占到GDP的17-18,一部分来自于税收的使用,一部分来自于各种强制性、半强制性或自愿的保险。这一消费的占比很高,不可小视,但很可能有相当一部分不在可支配收入的范畴里。这里还应该提一下,那些非强制性但绝大多数人都参与的养老金供款(如美国的401K)和健康保险,对这些开销应算在家庭可支配收入之内还是之外,各国之间似乎缺少一致的理解和口径。无论如何,“羊毛出在羊身上”,当人们认定眼下要为养老、医疗、子女教育(其中有些是未来才享用的)更多地缴款(包括税、保费等),意味着当下这些项目更昂贵了。那么,我们可否试测一下,以税费前净收入为篮子的、更为综合的物价指数及相应的通胀,也许更能反映“生活成本”。

从货币政策角度看,过去从资金供求关系分析物价指数的变动,后来则更多关注通胀目标制对通胀预期的锚定作用,有通胀预期理论。预期稳定了,通胀就能够稳定下来。这个预期也会包括对未来的住房、养老、医疗、子女教育等昂贵程度的预估。在人口结构变化之下,很多年轻一代上有老下有小,到手可支配的收入并不多,他们感觉未来生活压力大,这种预期不是现行通胀度量所能反映出来的。国民经济统计矩阵表明,政府所收的税费中,约80以公共服务形式提供给了公众,包括教育、医疗卫生、养老、安全、市政、环保等等,也还有一小部分在统计上仍属于公共服务,但个人/家庭往往不感知或不认账的。公众直接或间接获取的这些公共服务的量与质均与价格变动有关,从而在概念上是有通胀或通缩的。有人问,加大政府补贴是否会改善这方面的预期?如果从理性预期出发,消费者会预估到政府赤字和累计债务愈来愈大,其中包括地方政府赤字和隐性债务,则未来迟早要加税或用某种形式的通胀来由居民承担。还是那句话,“羊毛出在羊身上”。这就意味着,以劳动付出或用净收入为口径的通胀预期会与现行可支配收入口径的通胀预期不一致,随即就给货币政策出了难题。

相关的另一个难题是人们是否能感知或测度自己的税费前净收入?因为许多未拿到手的收入是预扣或企业代缴的,其中一些不甚透明。知道净收入才能更好感知这一口径的通胀,并产生预期。一般来说,人们其实不太容易知道自己的净收入是多少,但不同行业不一样。有的行业生产和分配过程比较简单,比如开出租汽车的个体,个体司机对毛收入是清晰可知的,也知道汽车的折旧成本(如果是公司的车需承担份子钱)、汽油费、维修费等成本支出,从而得出净收入,再交税、供养老金、缴医保等后就呈现出了可支配收入。美国的家庭农场也类似,收获的东西能卖多少钱,扣除种子、肥料、农机折旧,也容易算清楚净收入,这就可以知道净收入中多少用于养老计划、健康保险、个人所得税等支出,这些支出换取来的福利也是大致可感知的,如政府税收可能会管一部分子女教育(公立学校),也有一部分(如课外辅导)管不了。这之后才是可支配收入。不过,在一些复杂的生产过程中,确实很难知道自己的劳动贡献,按照自己个人的生产力究竟应获得多少报酬。尽管不好计算,但人们也是常常做横向对比的,即平均来讲,与同等教育水平、技能水平、工作强度的人相比,你如果干其它工作可能的收入水平是多少。

总之,收入的测度以及按什么收入来定义支出篮子并计算物价水平,会影响具体人们的通胀感知和预期,家庭可支配收入的篮子小了些,而篮子以外内容的价格上涨的较多。而从宏观经济模型来看,分类劳动者的平均净收入等于劳动对GDP的边际贡献,则是清晰、无可置疑的。

三、劳动付出的度量如何影响通胀的感知

前面提到了人们想测度的一个指标是通过工作换取特定收入的辛劳程度,或者说获得特定消费效用的劳动付出。经济学里狭义的效用函数大约是指一定量的支出所能换取到的消费满足度。广义一点可以是一定量的劳动付出所换取的消费满足度,再广义一点还可包括少劳动、多休闲多换取的综合满意度。应该说,“效用”没有令人信服的确切定义,已有人证明“效用”无法定量测度,只可排序。但付出/效用(之比)的概念显然与通胀有关联。有的人爱打比方,说他一年收入(不吃不喝)只够买一间厕所(约5平米住房),那么如果几年后他要用两年收入才够买一间厕所,是不是一种通胀?当然,必须假定该人在两个时段的劳动技能、劳动强度、效率是一致的,即等量或可比的劳动付出。也就是说,要从产生效用的广义物价和劳动付出所换取的收入两个方面(或者两者之比)来了解生活水平的通胀效应,即用更多的劳动付出换取同样的消费效用意味着通胀。

还有一种付出,是受教育、技能培训和学习,它在一定程度上是为了竞争工作岗位。随着横向竞争的加剧及自动化、机器人、AI的发展,人们必须对自己进行教育投资才能有竞争力。这一方面增大了劳动付出,另一方面增加了人们支出结构中的投资组成部分。

经济学已有不少文献提及或讨论过“休闲”的概念及其函数关系。人们需要休假,重回伊甸园等说法表明休闲能产生效用,而不仅是多干活、多挣钱、多花钱就买来了生活水平的满足感。但我们目前经济学里的物价指数和通胀概念还难以应对休闲。你如果出门休假,则交通、旅馆等支出均通过价格加以反映,并形成效用,也有通胀测度;而如果你在家养神、听音乐(不是新买的)、看本书(从图书馆借的)、与家人聊天,即便很具满足感却难以计价进入效用,也没有通胀计量,对GDP也无任何拉动。不知未来能否出现一个创新型经济模型来应对这一难题。但一个可以大致肯定的关系式是:在某种均衡点附近,休闲和劳动时长是此消彼长的(互补的)。如果很多人在工作中加班加点越来越多,上下班通勤时间越来越长,退休年龄不断后移,休闲也必然更少。这听起来像是上述用更多的劳动付出换取更少的消费效用,这在概念引申上应该是一种通胀。尽管现行通胀统计及分析未把这种概念和关系纳入其中,但仍可提示去关注我们最终想测度的是什么,如何解释某些群组感觉生活艰难、满意度不高的现象,以及这对货币政策的含义。

四、基准、可比性(comparability)和参照系

通常,物价指数中各消费组成部分都有其权重,权重是可测度并及时调整的,这在数理上支持了跨一个年度纵向比较的可比性。跨多个年度的比较则是多个跨一年比较的积分(累积)。但这种数理上的科学性并不等同于人们的通胀感知及预期的效果。当消费结构出现很大变化时,处理基准和权重的方法论受到挑战;科技快速发展带来的性价比变化有可能高估通缩的程度;再加上上述跨期纵比的科学性与人们常会横比的选择不一致,这就带来了争议之处。不能简单地去批评消费者说公式是对的,消费者是错的。因为常要研究的是消费人群的通胀预期及预期下的行为,尽管说跨期纵比的公式是对的。

度量通胀及物价指数实际上意在比较,因而涉及可比性;作较长时间的比较,涉及选用的基准,是纵比还是横比。这不仅涉及概念和方法是否科学、准确,即可比性问题,还需要考虑多数人的选择倾向,因为他们选用的比较方式形成了对通胀的感知及对未来的通胀预期。

观察多数人作比较的习惯,比如,计算机去年的CPU速度、内存大小、云存储空间,和今年都不一样。如果考虑摩尔定律,从计算机这一项而言,以性价比衡量,生活水平纵向比应该是大幅提高的,如果从五年以至十年、几十年来看,会有更加明显的负值通胀。但多数人实际上是平行比较的,即横比的,看同事、周围的人使用的计算机性能,如果自己的计算机比同事的性能低,就会感觉是不是生活水平显得差了一些,而不是完全靠纵向对比。

这个例子可以推广到其他一些内容,比如寿命。往回追溯20年,中国平均预期寿命在71岁左右,现在平均预期寿命77点几岁,很快就会增加到80岁。是不是凡是活到70岁以上的人都会很满足?因为不管怎么说已经比上一代人活的长多了。但是实际上多数人都活到70岁以上,如果现在70岁去世了,大家会说英年早逝;几十年前,如果70岁去世了,大家认为挺长寿的。这种对比说明,人们并不按严格的纵向数学公式或统计定义形成他们对满足度的感知和预期。

从寿命会引出养老金的通胀问题。上一代人60岁退休,平均寿命只有70岁,无论养老金是政府提供的、个人账户的,还是其他年金、个人寿险的,大约需要用几十个工作年头的积累去支持10年左右的养老就够了,而现在需要支持将近20年。未来即便退休年龄延长,使这种情况略有缓解,但整体上工作群体用于养老方面的支出仍会越来越多。虽然这些支出有一部分可能不落在个人可支配收入范围,但在平均值上,都是劳动者自己劳动创造的,“羊毛出在羊身上”。

这就涉及资产价格问题。如果股票很贵、债券收益率也很低,那么人们为养老投资几十年,但能够领取到的养老金数量是不足的。反过来说,在当前的净收入中,用于预筹养老金投资的钱还要花得更多,才能达到可比的养老生活水平,这就是一种价格上扬。医疗方面,可能大部分医疗费用都要花在人生的最后阶段,因此医保费用也具有长期积累性质,其回报都与资产价格有密切关系。同理,在教育方面,人们往往用横向比来形成对未来就业机会和前途的预期,而不是和上几代人纵比。这需要更长时间的就学,追求更高的质量,从而花更多的钱。不管是公费(“羊毛出在羊身上”)还是自费,都会有通胀或类似通胀的感知。

资产价格的变动趋势不确定性很大,特别是近期这一轮资产价格变化的不确定性在很大程度上与新型大型科技公司(BigTech)有关系。2001-2002年曾出现纳斯达克泡沫破灭,当前是否有泡沫,大家各持己见。如果有居高不下的资产价格泡沫,会使当前的投资变得很贵,而当前净收入中的投资又是当期或者跨期消费支出的必要组成部分(不管在不在可支配收入范围内),在概念上都跟广义通胀有关系。此外,也跟收入分配有关系。

简而言之,过去投资品价格和资产价格可另行考虑,现在再这样做恐怕已经不行了。未来养老金和医疗支出都很大,依赖投资回报且具有长期性。资产价格除了影响到企业的扩大再生产,还涉及基础设施、环境保护等公众性消费问题,不纳入通胀考虑已经不行了,但怎么纳入还需要研究。通胀及其测度问题面临若干挑战。过去看似很成熟的通胀度量,现在看来并不理想。当前的度量显然存在着忽视投资品价格和资产价格的问题。

当前不少国家的货币政策面临着不能有效达到通胀目标的问题,无论使用的是标题通胀(headlineinflation)还是名义通胀(nominalinflation)。近期美联储货币政策目标转向了平均通胀目标。如果按过去的度量方法得出的通胀很低,而资产价格上升得比较多,会出现不可忽略的结果,货币政策的设计和响应难以坚称与己无关。总之,需要明确要达到的目标,以及如何对目标进行测度。测度对于经济社会而言是相当复杂的,可能需要更广义的通胀概念;如何对通胀进行测度,值得进一步深入的研究。

Since he referenced Richard Koo, i went and checked him out. He cut his teeth during the Latin American debt crisis, and then was invited to a Japanese research institute during the Japanese lost decade. His main contribution is the idea of balancesheet recession. Here is a nice interview of his.

I actually watched a NHK documentary on postwar Japanese economy after that, very nicely done. First impression: US plays such a major role in Japanese monetary/development policies. When the war first ended, the alies want to make it an agricultural industry, any war related production is prohibited. Then the cold war come along US feel that they could use Japanse as a counterbalance to Russia in China, weaponary production are encouraged all of a sudden. During the war, Japnan caltivated engineering talents who almost could not find work in the post war economy until the higher ups decided that they want to invest in heavy industry. When Japanese auto industry get too popular, the US workers get upset and US forced Japan to lower their interest rates, against their own best judgement. Because when Japanese interest rate is lowered, there would be more credit in the system, there would be assumption by the japanese people. Hopefully, those consumptions include make in US product. Also the inflation would make it more expensive to make things in Japan, raising the price of make in Japan product. Althogh people in Japan has already realized that they could not keep the interest rate that low for any longer, the 1987 stock market crash happened, and leaving JP central bank with only bad options. During the boom years, Japanese businesses accrued huge amount of debt because they feel the bubble would go forever. Actually if you look at that documentary, you would realize that the speculators are the same group of people, in China, HK, Singapore, US or Japan. This is a side note, i would develop later. In 1987, the central bank of Japan feel that they could no longer just let the bubble grow and they raised the interest rate. The stock market crashed, so does the real estate valuation. When the asset price goes down like that, in the balancesheet, all those companies with debt would seem insolvent although they do have the income stream to service that debt. That is what Koo calls balancesheet recession.

For nearly 2 decades, all what companies did was to pay off their debt. The economy is mostly supported by government presurement. Yet the toll is much more than that. On a psychology level, people must feel like that couple in “The Necklace”: one mistake, enslaved themselves for the decades to come. Even after they paid off all their debt, they would never be endebted again, slowing down the economic development. Another is literally a generation of people wasting their lives. An entire generation of Japanese people who can’t be integrated into the society, with nothing better to do than to wait for their death. That is the real tragic part of the entire thing.

Koo’s idea of balancesheet recession is that during this kind of recession, govenment has to increase its spending in order to provide companies income stream to pay off their debt as soon as possible. Only after the companies has sorted out their balancesheet, can the government begin to sort out its own. I also watched Koo’s accessment of China’s situation, he seems to suggest that we are doomed to get into the middle income trap. He suggested the leadership heed Deng’s words: hide ones strenghth, bide one’s time. Wait until China goes through the middle income trap, and then flex its muscles. Becase at that time, the country would be strong enough to set the rules. Not a minute before that moment. Yet here we are, an agressive deplomatic team, an agressive expansary policy that is begged to be pushed back against. How stupid they leadership is?

Let me develop an observation of mine: the society is made up with different human spieces. For instance, the speculators of a society are pretty much the same human being, just in different nationalities. Essentially, economical policies seems to favor one kind of people other the others. In that NHK interview, all those executives seems to look back and regret they did not do what they know was the right thing to do. Are we really capable of independent judgement? Seems to me that is hard to comeby. For instance, the digital currency stuff. While I prefer to stick with cash, because it does not leave a trail of transaction records that can be analyzed and figure out who I am as a human, it is really no longer a choice. The ATM machines are no longer maintained by the banks due to the costs associated with it. Venders refuse to collect cash, institutions move their entire accounting facility online etc. The situation is such that while I have my preferences, there is really no longer an opportunity for me to carry out my prefered choice, rather, all I have to do the same thing as does everyone else. THAT IS HOW A BUBBLE GET ITS MOMENTUM. If you look at the interviews of those people who facilitated the Japan bubble, you will see that they know exactly what the right course of action is, yet they don’t have the avenues to carry out the right choice while the wrong choice is the one require zero effort.

I remember Meltzer talked about how one should make life decisions independed of government or fed policies that probably is the best approach to life. While as an aggregate, opportunities avail themselves in a temporally limited fashion, therefore, debt and credit policies are extremely important for an aggregate. For instance, India develop its software talent, Japan develop its automotive industry etc. For industry building at that level, monetary policy is the only way to go, yet for individual develpment, I don’t think opportunities are temporally concentrated. Rather, it is more depends on your judgement. Judgement is something that comes with time.